My last post was designed to offer historical precedent for the rise of China. It might have achieved that. But it raises more important questions. The most important is: how do financial systems cope with a world of deflation (created by both China and technology)?

The solution has resulted in a bi-polar personality for financial markets: capital destruction and capital accumulation all in the context of low interest rates. Indeed, deflation and its consequences is the key lesson global financial markets must adapt to. This offers substantial challenges.

Deflation: China and Technology

The Long Depression, as described last week, was a period between 1867 and 1893 characterised by strong real economic growth and price deflation. It was a function of a massive productivity improvement as the United States opened up the land of the Mid West to agriculture.

This period is now being mirrored in the opening up of China. China too, through investment in productive capacity, has enjoyed strong real growth but relatively benign price growth. Consequentially, as was the case in the US, China is exporting deflation to the rest of the world, in conjunction with an improvement in technology. It is worth highlighting again the comments of a contemporary observer, David Ames Wells:

“The economic changes that have occurred during the last quarter of a century – or during the present generation of living men – have unquestionably been more important and more varied than during any period of the world’s history … Some of these changes have been destructive, and all of them have inevitably occasioned, and for a long time yet will continue to occasion, great disturbances in old methods, and entail losses of capital and changes in occupation on the part of individuals. ”

The combination of the US opening up and new technology like the telegraph combined to create much higher living standards (the prices of goods and services plummeted) but similarly created “destruction”, ”great disturbances in old methods” and “entail losses of capital.” Today seems no different.

Not only have living standards unarguably risen in the last twenty years, the UN for instance estimates in its Human Development Index that living standards have risen 2.5% per annum in the last 20 years, but material falls in prices have also occurred. My favourite demonstration of this phenomenon is the 42-inch LCD television. According to US data, between 2006 and 2011, prices fell from $4200 to $800. They’ve fallen further since.

But as in the late 19th century, it’s not just China. Computing power has increased dramatically and has made many basic processes much more efficient, this has destroyed business models. Follow this link to observe how long it has taken for computing power to catch up with the human brain. The link highlights that the biggest leaps in absolute terms are occurring now.

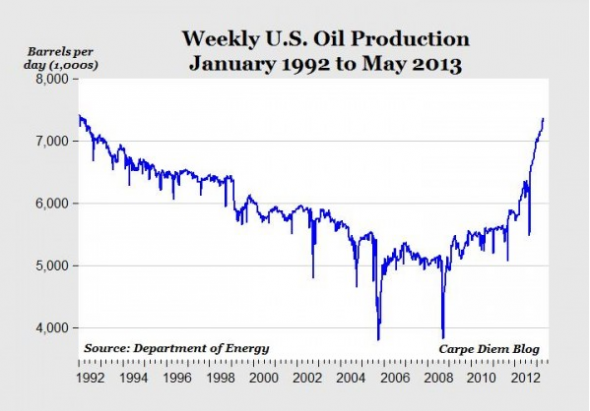

Or similarly, we’re now seeing the emergence of falling energy prices due to either an increase in production of fossil fuels or a decline in price in solar. The chart below shows weekly US oil production rising to the same level as 1992, while the price of solar panels per watt has fallen from $77 in 1977 to $0.77 in 2013.

These changes in production costs do two obvious things: they increase living standards and they destroy business models. Business models that are dependent upon the assumption of rising or stable prices for inputs or final products. The result is a mix of capital destruction and accumulation.

Capital destruction

The destruction of capital is an inevitable trend in a deflationary environment. Strong and persistent deflation destroys the assumptions of existing businesses and financial models.

This is most obvious in the developed world’s industrial base: the assumptions underpinning the original investment have been destroyed by China’s investment. This process will now be mirrored in energy production. So much existing capacity will either need to be re-engineered to compete or substituted and the capital destroyed.

In turn, this creates real problems for the financial system, particularly the banks. The banking model in the US has clearly had to change. In part, this is due to regulatory change and the financial crisis. But I would argue it is also a response to deflation. Many of American banks’ key clients are no longer their key clients. When blue-chip clients are able to borrow at ultra low rates from the corporate bond market, bank loans are squeezed out. For instance, corporate bond underwriting has risen 8.7% since 2009 while commercial loans by banks have risen just 1.9%.

As a result we’ve observed a change in business model amongst banks who are now focusing more on transaction based fee-income and also returning to the scene of the crime in the form of mortgages. For those banks who are unable to make such a strategic shift it is becoming more difficult to stay in business. Since 2008, 490 US banks have failed and been subsumed into other banks.

As we’ve seen in recent years, deflation has caused the destruction of a lot of capital.

Capital accumulation

But this process of deflation through higher productivity has similarly led to the accumulation of astonishing volumes of financial capital. There have been two drivers of this process.

The most obvious has been the productivity improvers. China has run substantial surpluses despite its extraordinary investment. It is too competitive and so able to generate substantial piles of cash. Partly, these surpluses have been a function of the currency, but largely are a reflection of the productivity gap between China and the rest of the world. Similarly, companies such as Apple have also generated enormous cash balances. Apple’s $400bn of market cap reflects $150bn in cash and just $4bn of tangible assets. Apple is hyper-productive and capable of producing surpluses for which it has no clear use.

But there has also been a global response to deflation which has led to higher savings rates. This is a rational process. On the assumption that prices will be lower tomorrow, households save cash. This process has been most extreme in countries with ageing households and industrial bases that have required substantial change to cope with competition: Japan and Germany.

In an environment of higher capital productivity and deflation, this accumulation of financial capital has not led to a consequent increase in investment in productive capital. Productive companies don’t need more capital: big mining and energy companies have been out of capital markets for some time. While unproductive companies are never going to be able to access markets.

If deflation is inevitable…

If deflation is inevitable, then current low rates are also inevitable. I’ve argued before that higher rates would be valuable. Today, I’m arguing the opposite. Higher rates are simply not possible in this environment. The unproductive part of the economy, the old industrial base and US banks, cannot cope with higher rates. We’d just have more panic. Indeed, higher short term rates would only lower long term rates. Price expectations would necessarily fall further than they are now.

This has substantial consequences for asset markets. It means a substantial shift out of bond markets is unlikely. It also leads to a continued rally in the equity market: long term interest rate expectations are too high. The equity risk premium at 5% is above the historical average of 3% and the dotcom height of 1%. This is entirely reflective of interest rates that are too high. The rally will be concentrated on valuation, not growth. Growth is nearly impossible in a deflationary environment for most global capital.

It will, as in the history of finance, create bubbles. I suspect it highly likely the prices of homes in a number of impacted economies reach levels seen in 2006/07. As bubbles end, inevitably there will also be panics and more trouble for banks. But such panics won’t change the fundamentals of too much capital. Prices will return to higher levels.

How can you create inflation?

There is only one means of creating inflation: higher wages. Until there is a deficit in the supply of labour, deflation is inevitable. This highlights Australia’s great strength. Rising wages are allowing positive inflation, despite deflation in goods, particularly those that are imported. The best means of maintaining rising wages is a currency that reflects market valuation, which in turn reflects productivity and encouragement and support for the services sector.

The alternative, creating manufacturing competitiveness, leads to one thing only: a lower living standards. The winner in manufacturing will be the most cost efficient. For emerging markets, with low incomes, transitioning to higher incomes, that’s not the worst thing. For the developed world it’s a disaster.

Alternatively, you could create really negative rates, say -5%. That would start to make capital a bit more scarce.